I had the privilege of attending the Canadian Annual Derivative Conference in Montreal yesterday. It’s an event I’ve been attending for at least 20 years, though this was the first time my perspective was that of a former options market-maker rather than an active one. As usual, I learned about unfamiliar aspects of the market from a wide range of speakers (and of course, enjoyed the cocktail party), but one presenter’s comment incensed me. She crowed about how she enjoyed some sort of special status with “upstairs” options dealers that allowed her to get hidden price improvement. Guess what – any options trader, large or small, can often get price improvement by using some basic common sense.

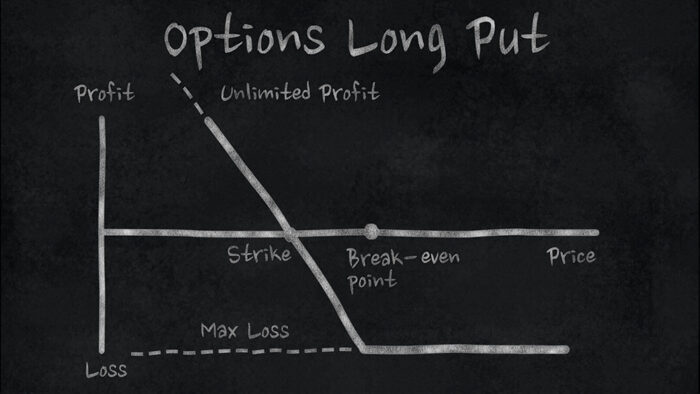

The important thing to keep in mind is the concept of “fair value.” When a market maker posts a two-sided market, you can assume that his fair value is the midpoint of those quotes. Market makers are in the business of buying below their fair value and selling above it. They are posting the ideal price that they want to trade that particular contract at that moment, but they are often willing to accept a smaller profit above or below their fair value. That is price improvement.

For those of you who trade US options on the IBKR platform (and if not, why not?), you should already be quite familiar with price improvement. It is literally built into our routing. Thomas Peterffy explained it in detail in a podcast we taped about a year ago. I’ll let Thomas explain some of the mechanics: (the full edited transcript is available here):

[A market maker] makes a bid and offer for each option and submits them to the exchange as limit orders. He hopes that he will buy and sell a lot of options at those prices. As the stock prices move around, he moves his market or quote with them based on the option formula he is using. This is of course all done by computers, as millions of auction prices are moving around all day long and the response time for any event must be within milliseconds or microseconds.

When that market maker gets an opportunity to buy an option without pushing the price … higher at the exchange, that is a huge benefit to him that he is willing to pay for. IBKR is trying to give him that opportunity and give its customers a really good price.

Now, how does that happen? Anytime IBKR receives a customer order to buy or sell an option, it begins an IBKR auction without disclosing if the order is to buy or sell. It immediately requests a quote from its 15 liquidity providers. The 15 in the system will send an automated response within milliseconds. Those codes will reflect each market maker’s relative willingness to do the trade. The one who will want to buy the most will bid highest and the one who wants to sell the most will offer lowest.

Along with their quote, each liquidity provider also tells IBKR at which exchange they would like to consummate the trade. IBKR now notifies the winner and takes the options to the directed exchange and begins an exchange auction. At the exchange auction, the winner of the IBKR auction is compelled to provide the same price that he won the IBKR auction with. If nobody else betters that price IBKR does the trade with him, and the customer order is filled. On very few occasions it happens that the exchange on the exchange auction somebody provides a better price and in that case our customer will get that better price.

Bottom line, in the US, where there are many competing venues and established exchange auction processes, it is quite common for our customers to receive prices that are better than those posted on the national best bid/offer (NBBO). It is not always the case, of course. For example, if a stock is racing higher, call sellers don’t need to improve their offers. Also, if a spread is a penny wide, there isn’t much room for improvement.

As Thomas noted, a market maker is posting a multitude of prices at any given time. Consider the number of contracts that are listed on the most popular options, then multiply them by the number of stocks or ETF that the market maker is responsible for. It is impractical, especially in a fast-moving market, to post one’s absolute best price for every contract. Instead, they often utilize a slightly wider spread, then respond to bids and offers as they come in.

In the specific case of Canada, the market structure is very different than in the US. Listed options trade only on the TMX, there are fewer market makers, and there are also fewer active traders who tighten the spreads with their resting limit orders. Furthermore, large orders (usually 250 contracts or more) do not need to be exposed to the market for price improvement. These are so-called “zero-second crosses.” The theory is that sophisticated institutions, who trade “upstairs”, can decide for themselves whether they are receiving fair prices as long as they respect the posted markets at the time.

There was some logic to this idea when crosses needed to be exposed by phone to the market. The process was slow – it could take several minutes — and thus rife with information leakage. But zero-second crosses bifurcated the market between small and large investors. It then became archaic in its own right once the exchange developed the capability for complex orders to be exposed for mere fractions of a second. But: since the process suits the big banks – many of who are not active market makers – and their customers haven’t advocated for change, the rule persists.

Under that framework an institution can negotiate with a bank’s trading desk who uses the posted market as a guide. If it is a relatively illiquid contract, the spread might be relatively wide, allowing the dealer to improve over the posted price. Even so, the bifurcated market means that market makers are disincentivized from leaving too much size on the book at tight spreads, since they risk being run over by large orders on which they can’t really participate.

As a result, that leaves plenty of opportunity for small traders to do their own price improvement. Remember, market makers are almost always willing to trade any price that offers them a reasonable profit around their fair value. Let’s say a random option is $1.10-$1.30. That’s a relatively wide spread, but not truly uncommon. It is reasonable to assume that the market makers agree that the fair value is thus around the $1.20 midpoint. Don’t you think that one of them would be willing to sell to you at $1.25?

There is an easy way to find out – bid $1.25. Market makers’ software is generally programmed to hit that bid quickly. If they all think it’s worth $1.20, there is a real incentive to be the first to hit a $1.25 bid. Maybe not, but maybe they’ll hit a $1.26 bid, and so on.

I’ve discussed this in several forums with small investors, and there is a common misperception that the market makers will move their prices rather than trade with them. This cannot be further from the truth. Market makers only make money when they trade and are definitively not in the business to avoid trading with small orders. That is their bread and butter. Sure, if the stock in question is moving, the $1.25 bid might no longer be appealing. But more often than not, in a stable stock with options that have a relatively wide spread, price improvement is not that hard to achieve.

I’d like to think that this should have an element of common sense to it. It fits so perfectly with my experience as a market maker that it is perfectly logical to me. Small investors who trade options should always be seeking the price improvement that is readily available to them, regardless of marketplace. It’s there for the taking.

Disclosure: Interactive Brokers

The analysis in this material is provided for information only and is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy any security. To the extent that this material discusses general market activity, industry or sector trends or other broad-based economic or political conditions, it should not be construed as research or investment advice. To the extent that it includes references to specific securities, commodities, currencies, or other instruments, those references do not constitute a recommendation by IBKR to buy, sell or hold such investments. This material does not and is not intended to take into account the particular financial conditions, investment objectives or requirements of individual customers. Before acting on this material, you should consider whether it is suitable for your particular circumstances and, as necessary, seek professional advice.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Interactive Brokers, its affiliates, or its employees.

Disclosure: Options Trading

Options involve risk and are not suitable for all investors. Multiple leg strategies, including spreads, will incur multiple commission charges. For more information read the "Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options" also known as the options disclosure document (ODD) or visit ibkr.com/occ

Join The Conversation

If you have a general question, it may already be covered in our FAQs. If you have an account-specific question or concern, please reach out to Client Services.