When Paul Volker ascended to the Federal Reserve’s helm in 1979, he had strong tailwinds for fighting inflation. At the time, monopolies were being dismantled and businesses were rapidly moving manufacturing to countries with low labor costs.

In a significant reversal, businesses are aggressively returning manufacturing to the U.S., while policymakers’ concerns about monopolies have been mostly limited to big tech. As businesses reshore manufacturing, they, like many employers, are struggling to find workers for their new factories as a historically tight labor market is driving wage gains in many industries. Foreign countries are also increasing their investments—and demand for workers—in the U.S. This trend is supporting domestic wage pressures and inflation while also stoking demand for construction materials for new factories and automation technology.

This commentary examines the history of offshoring, monopolies and wages, and it assesses why businesses are increasingly reshoring. Finally, it addresses the potential impact of reshoring on inflation.

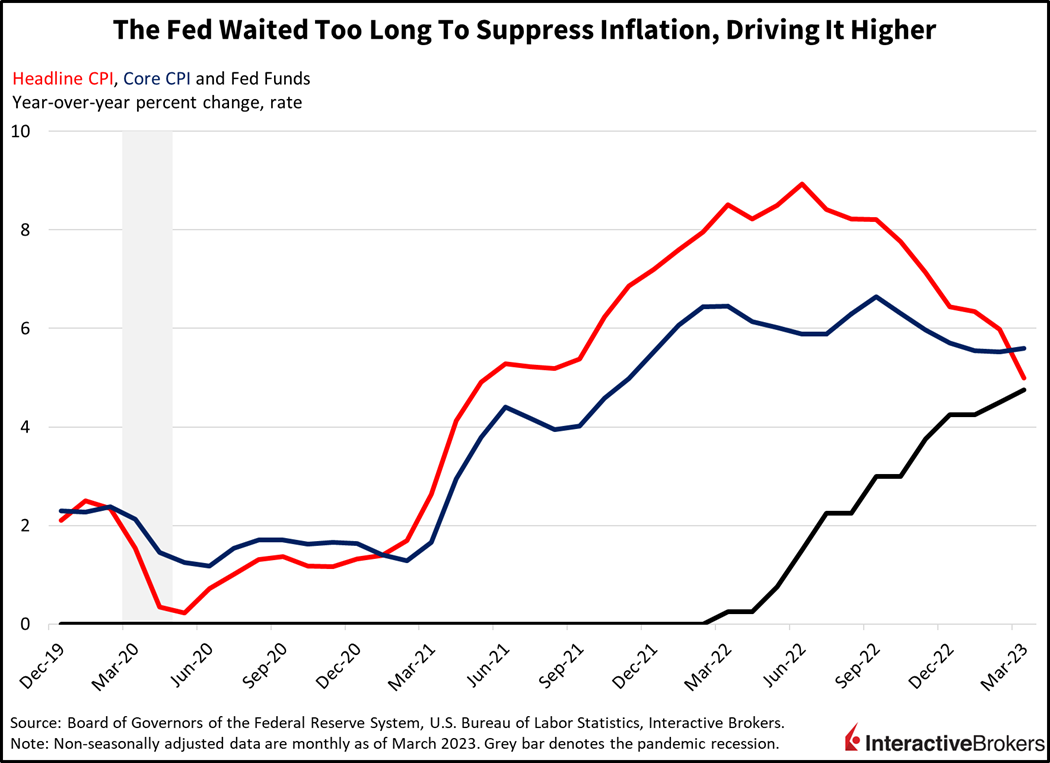

Fed Delay in Fighting Inflation

After remaining below 4% since late 2008 and dropping below 2% in 2020, both Core and Headline CPI inflation gauges staged rapid increases. From the 2020 lows, headline inflation hit 9.1% year-over-year (y/y) last June and Core CPI reached 6.6% y/y last September.

Figure 1

In hindsight, the Fed mistakenly believed that inflation would be transitory as illustrated by the following:

- The Fed started its war on price increases with a 25-basis point (bp) fed funds hike in March of last year, lifting the target rate to a range of 25 bps to 50 bps (See Figure 1).

- Core CPI and Headline CPI were already at 8.5% and 6.5%, respectively.

- This first rate hike occurred exactly one year after core PCE inflation climbed above the Fed’s 2% inflation target.

- The Fed quickly followed its March hike with a 50-bp hike and then four 75 bp hikes before moderating its pace of increases and reaching the current target of 4.75% to 5.00% in March of this year. The Fed also began reducing its balance sheet to reduce liquidity within the economy.

- Inflation has continued climbing and didn’t show signs of moderating until late last year.

Multiple years of deficit spending, the Covid-19 pandemic, global supply chain issues, prices for energy and other commodities, geopolitical frictions and unexpected labor shortages created a virtually unchartered combination of events that the central bank appears to have downplayed in previously labeling inflation as transitory.

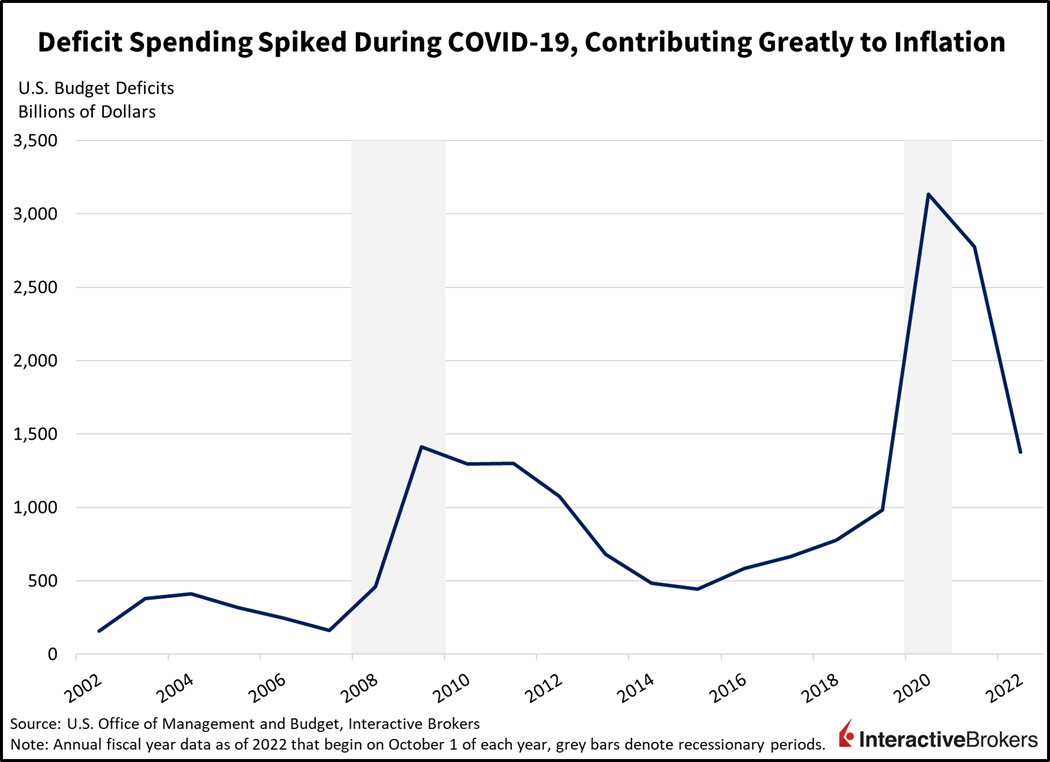

Fiscal Stimulus Sets New Records

The bulk of fiscal stimulus—and a new record for attempting to boost the economy—occurred during the depth of the Covid-19 pandemic, with $3.1 trillion in deficit spending in the fiscal year that began in October of 2020 to avert an extended recession. However, deficit spending has occurred every year since a three-year period of surpluses that ended at the start of fiscal year 2002.

Figure 2

Pandemic Sparks Consumer Spending Binge

Individuals who sheltered at home during the Covid-19 pandemic splurged on home office equipment, entertainment technology and home renovations, creating a significant supply and demand imbalance for most types of goods. Additionally, measures to contain the virus, such as closing entertainment venues and restricting travel, created pent-up demand within the services industry, which is still experiencing persistent inflation.

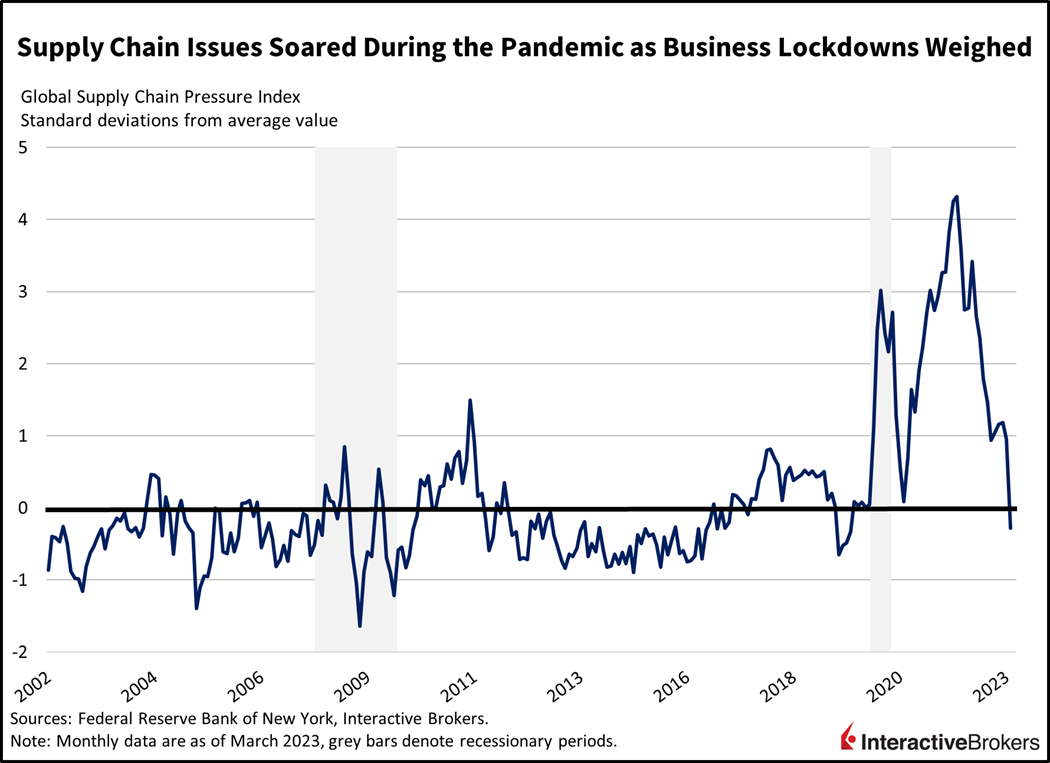

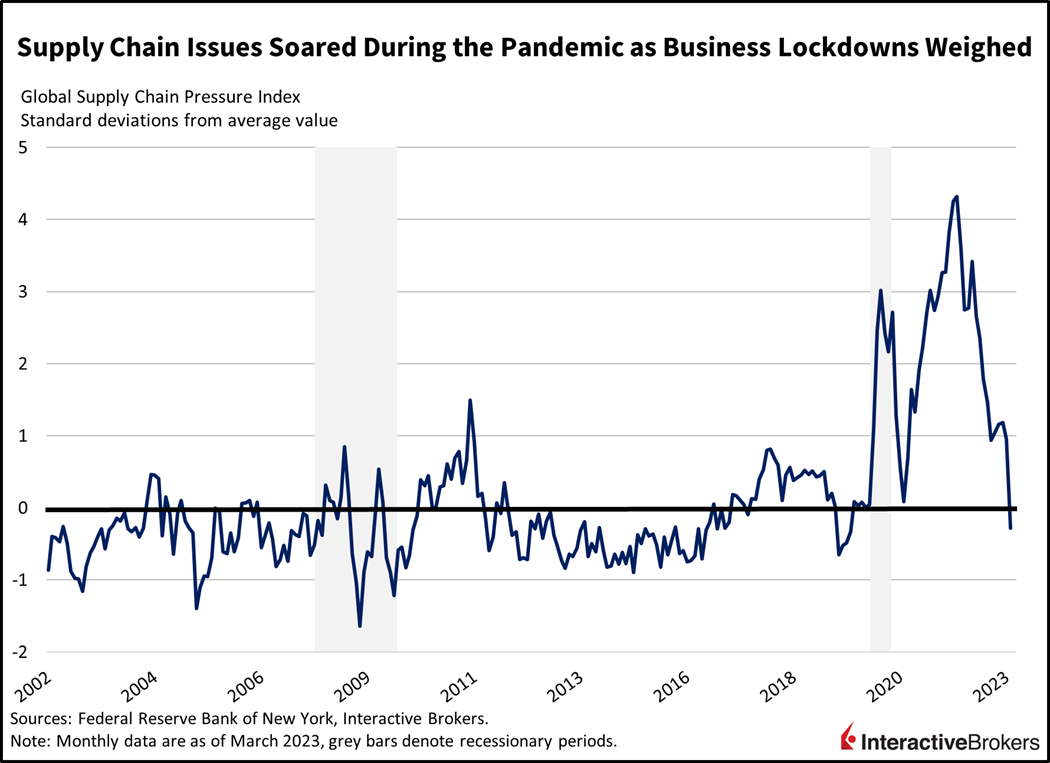

Supply Chain Problems

Meeting the strong demand for consumer goods during economic lockdowns and then fulfilling the increased demand for entertainment, travel, dining out and live entertainment when pandemic restrictions were lifted became increasingly difficult because of supply chain issues. These issues were driven by prolonged closures of factories in the U.S. and across the globe, with China shutdowns being notable because of their scale, length and severity. Supply chain issues impacted all sectors of economy. For example, U.S. automobile manufacturing came to a standstill due to a shortage of computer chips. Other shortages included baby formula, sanitizing wipes, lumber and even Christmas trees, causing prices for those items and other products to surge. Unfortunately, the worst of the supply chain issues lasted longer than many analysts had expected.

Figure 3

Labor Market

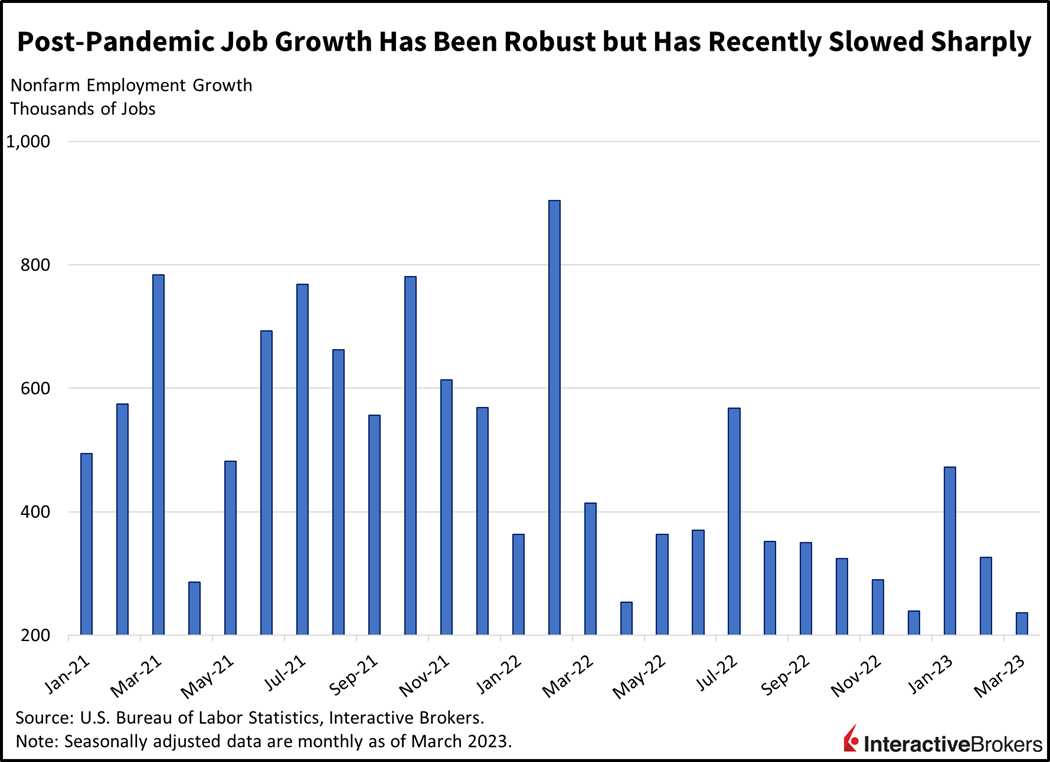

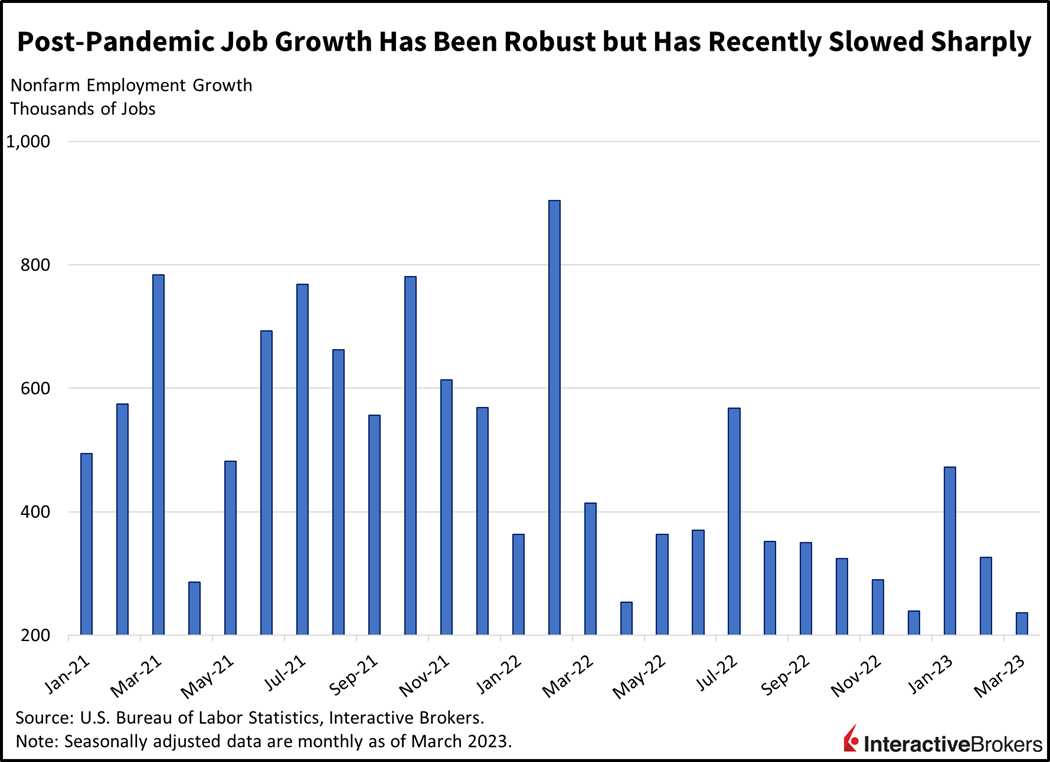

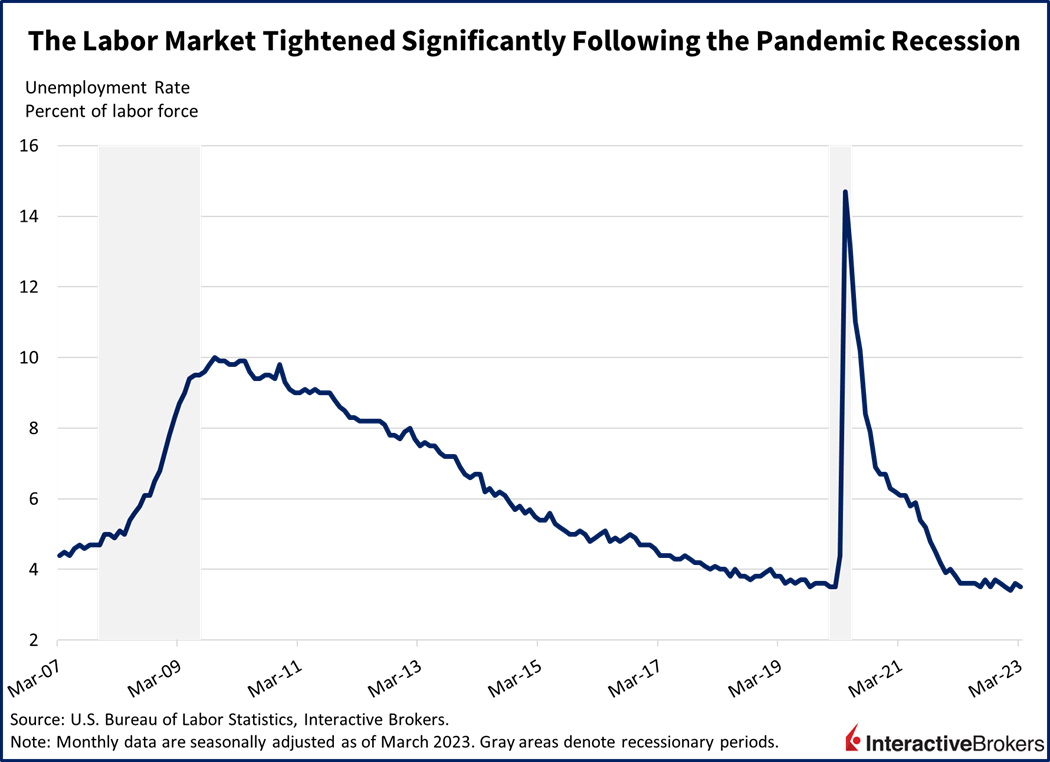

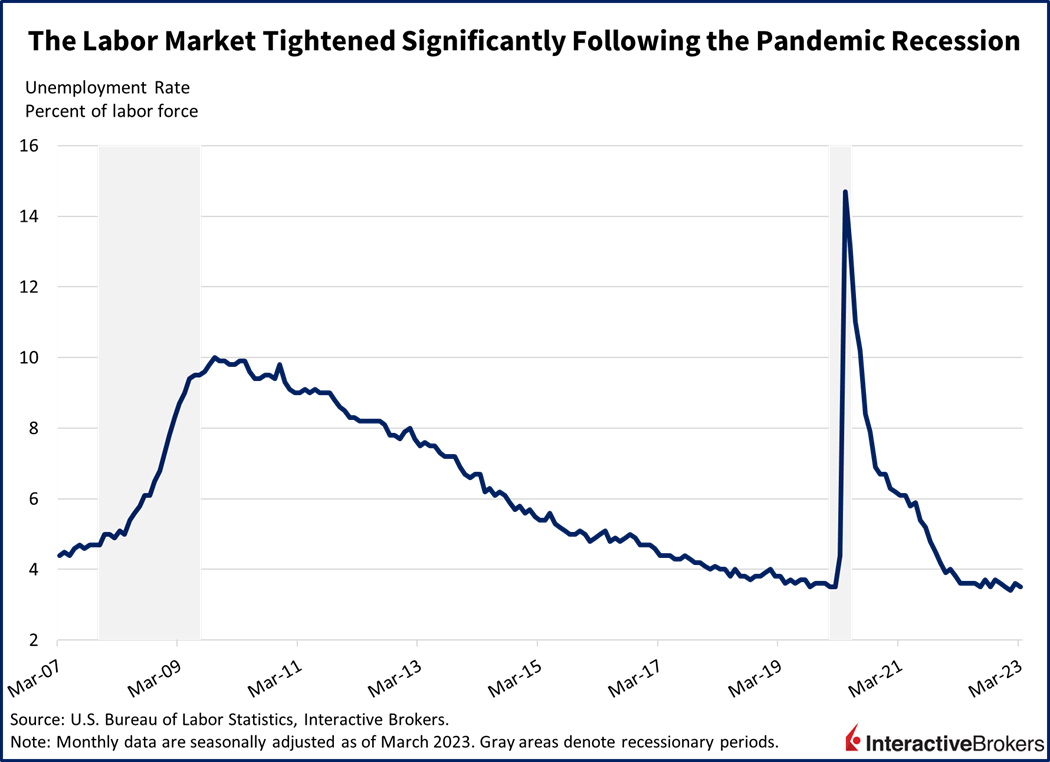

The labor market has been extremely strong with March being the 27th consecutive month of net job creation in the U.S., while the unemployment rate has remained below 4% for more than a year (See Figures 4 and 5.) The shortage of workers is a result, in part, of aging baby boomers retiring, but another factor exists: some working-age individuals have been pushed to the sideline by long-Covid while others, at least up until recently, have been afraid to venture into public workplaces because of fears of catching Covid-19. Other individuals hit the sideline after becoming discouraged about their income and growth prospects while a large mismatch in worker skills and skills required by employers also created issues. This labor shortage is creating wage pressures that in many cases are being passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices for goods and services.

Figure 4

Figure 5

Energy Prices Spike

The 2020 recession associated with the Covid-19 pandemic, supply chain issues, and the Russia invasion of Ukraine created a surge in energy prices. Energy is excluded as a component of core inflation gauges, but it has contributed to inflation across the economy by increasing businesses’ operating costs, including freight shipping, airline tickets, and running factories and offices.

A strong drop in energy demand during the depth of the Covid-19 pandemic caused oil to briefly trade at negative prices. This development caused investors to pressure energy companies to avoid creating an oil supply glut. Energy companies curtailed capital outlays needed for increasing production, thereby restricting oil supplies as demand for gasoline and other fuels increased when the economy reopened. Exploration and production companies also faced a shortage of equipment needed for drilling new wells because of supply chain issues. Finally, oil and natural gas supplies were challenged when exports of energy commodities from Russia were greatly curtailed because of economic sanctions instituted in response to the country’s invasion of Ukraine more recently, because OPEC + has made production cuts. Additionally, shareholders are increasingly pressuring energy companies to embrace environmental, social and governance factors, so many oil companies are shifting assets into clean energy.

Lessons from the Paul Volcker Years (1979 to 1987)

Paul Volcker became the Fed chairman in the summer of 1979 when inflation was 11% and still climbing. His monetary policy tightening took four years to bring inflation below 4%, and it contributed to two recessions, high unemployment and a spike in financial market volatility.

Those dire consequences occurred despite disinflationary tailwinds of monopolies being dissolved and manufacturers aggressively offshoring production to lower labor-cost markets. Today, neither of those tailwinds exist, making it more difficult for Fed Chairman Jerome Powell and the rest of the central bank to fight inflation.

Breaking up Monopolies and Deregulating the Economy

Various government policies resulted in increased business competition. With increased competition, businesses had less leeway to pass higher costs on to customers by raising their prices. This caused employees to focus on controlling wage increases.

- The Bell System under AT&T was broken into “baby bells” in 1982, which led to an eventual surge in competition from companies such as Sprint and MCI. Long distance calls were about 91 cents a minute in today’s dollars, but now are virtually free with voice-internet services.

- The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 reduced government control over various aspects of aviation, allowing for new carriers to enter the industry, which resulted in increased fare competition. By 1997, the dollar yield for airline operators in inflation-adjusted 1982 dollars fell from 12.3 cents in 1978 to 7.9 cents in 1997.

- The 1980 Motor Carrier Act allowed new competitors to enter the trucking business and charge whatever rates they could get.

- The 1980 Staggers Rail Act deregulated rail rates and other aspects of the railroad industry, allowing shippers to negotiate unregulated contract rates.

In Search of Low-Cost Labor

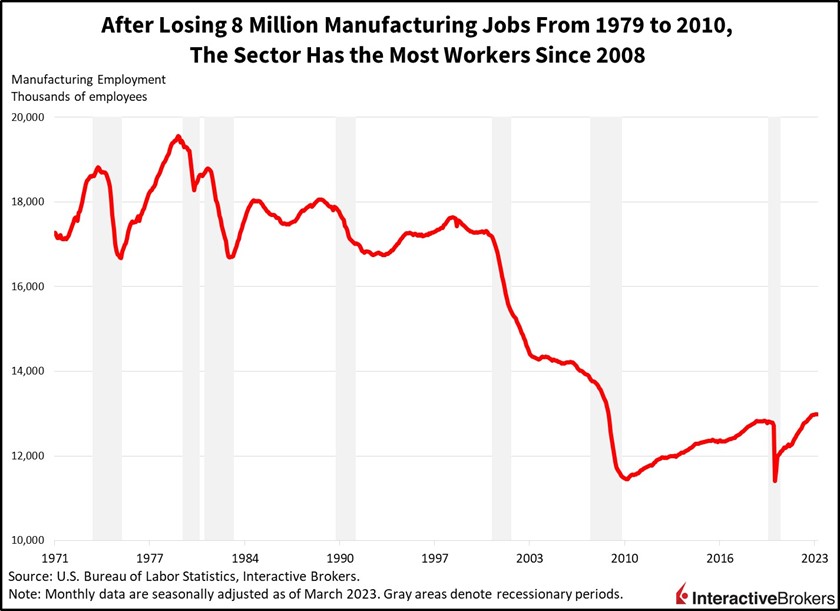

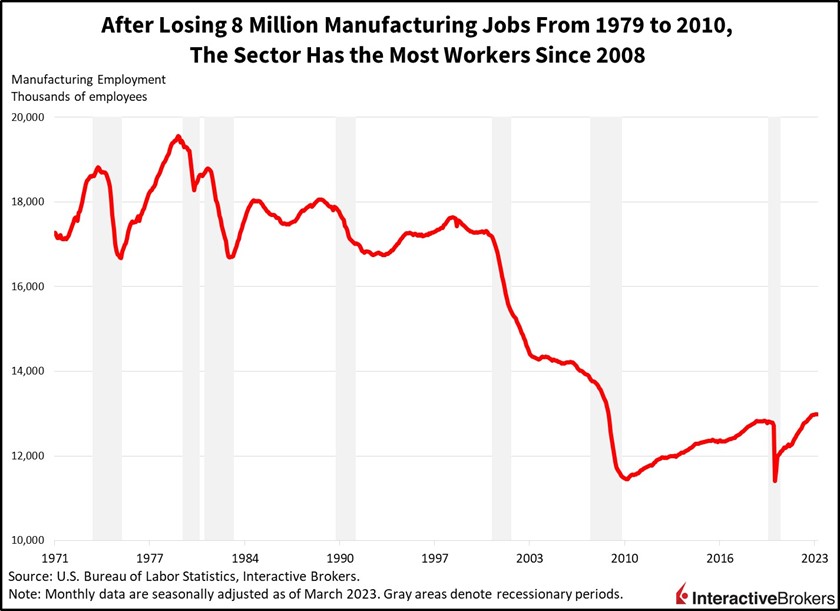

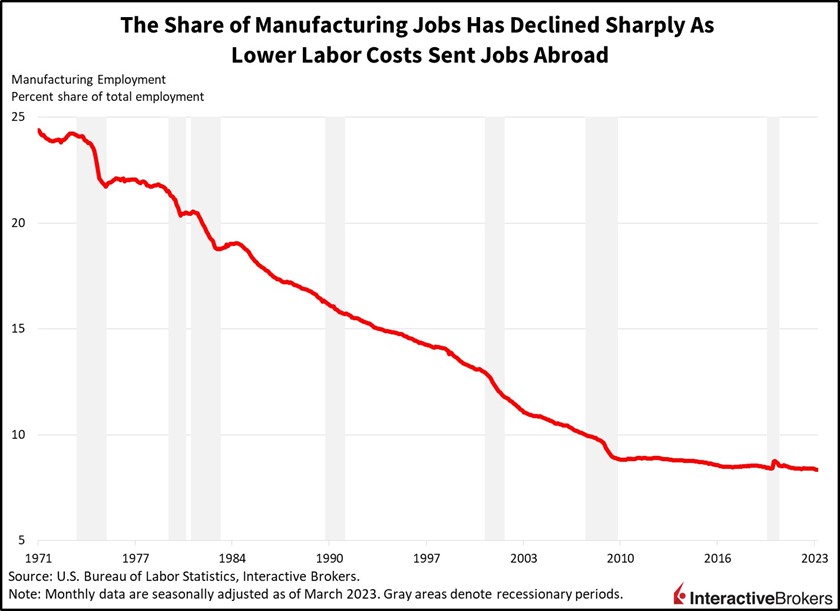

U.S. businesses have embraced offshoring production since at least the 1960’s when Mexico established its Maquiladoras manufacturing system and various Asian countries industrialized. Offshoring became more noteworthy in the 1970s when General Electric (GE) CEO Jack Welch emphasized that corporations’ primary responsibility is to shareholders. To that end, he not only offshored manufacturing to low-labor-cost countries, but he also provided training to GE vendors, helping them to follow suit. In many instances, offshoring during the peak inflationary years in the 80’s and 90’s allowed manufacturers to pay workers roughly $2 an hour instead of $20 an hour in the U.S. The shift to offshoring was dramatic:

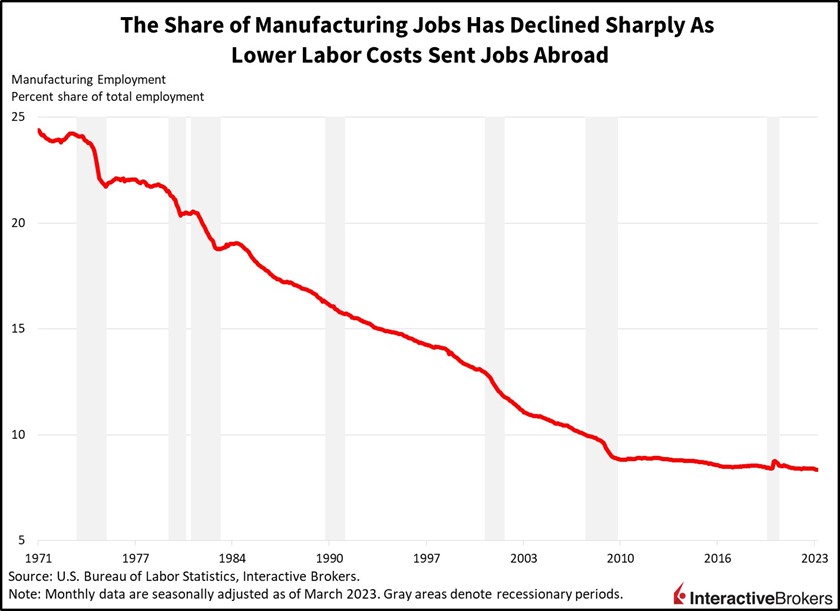

- More than 8 million U.S. manufacturing jobs were wiped away between 1979 and 2010.

- In the mid-1970s, manufacturing employment accounted for about 25% of U.S. jobs. That declined to approximately 8% today.

The Cumulative Impact of Volcker’s Tailwinds

The combination of deregulation and offshoring had the following two strong impacts on fighting inflation:

- Deregulation fostered increased competition—including price competition across the economy, limiting price increases. Moreover, labor cost savings from offshoring contributed to lower prices, perhaps at the expense of quality. Nevertheless, the lower prices from increased competition and offshore labor saved consumers and business trillions of dollars over the years.

- Deregulation and offshoring had a two-fold impact on labor wages. As deregulation increased competition in the U.S., businesses were forced to reduce their costs, so they showed more restraint in increasing employee wages. Employees, furthermore, had less clout to negotiate wage increases because they were competing with lower-cost foreign workers. Offshoring also weakened demand for American workers, which also contributed to weaker wage pressures.

Macro Headwinds Challenge the Fed

Today’s Federal Reserve is fighting inflation without the benefits of the large-scale breaking up of monopolies and a wave of deregulation that would spur competition to combat price increases. Furthermore, and perhaps more significant, the trend of offshoring has reversed, supporting tight labor market conditions and wage pressures.

Monopolies, Competition and Deregulation

With the exception of large tech platforms, including social media and search engine providers, few large companies have targets on their backs for regulators anxious to break up monopolies. For the most part, recent regulatory activity has focused on blocking mergers such as the proposed JetBlue takeover of Spirit Airlines. Unlike during the Volcker years, regulations, at least on the Federal level, are increasing with a renewed emphasis on environmental protection, including fighting climate change, and more recently, improving financial stability following the failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank.

Bringing Jobs Home

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing (TSMC) officials are preparing to spend up to $40 billion to build a semiconductor foundry in Phoenix, Arizona. It represents the largest foreign investment into the U.S. in the country’s history. The first phase of three phases of construction is expected to create more than 3.8 million square feet of manufacturing and office spaces. It will create 21,000 construction jobs and some 40 suppliers for the company plan to establish facilities nearby.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing (TSMC) officials are preparing to spend up to $40 billion to build a semiconductor foundry in Phoenix, Arizona. It represents the largest foreign investment into the U.S. in the country’s history. The first phase of three phases of construction is expected to create more than 3.8 million square feet of manufacturing and office spaces. It will create 21,000 construction jobs and some 40 suppliers for the company plan to establish facilities nearby.

TSMC isn’t alone in tapping U.S. labor as both foreign companies and domestic businesses are turning to local manufacturing. Even GE has made the switch after determining that shipping costs were offsetting savings from lower cost labor abroad and that efficient floor plans could reduce domestic manufacturing costs. The company first reshored water-heater production and has since reshored manufacturing of other products.

A Strong Trend

In a March 2023 survey by Xometry and Forbes, 55% of American chief executive officers said they plan to reshore operations and among those, 95% plan to do so this year. A wide range of factors is driving the surge in reshoring.

- Despite the recent improvements in the global supply chain issues, the survey found that 95% of CEOs believe supply chain disruptions won’t improve any time soon. While more efficient factories can make U.S. manufacturing more cost competitive, executives are increasingly emphasizing reliability over low-cost labor found abroad.

- Legislation such as the CHIPS and Science Act is incentivizing the domestic manufacturing of computer chips and other technology products in the U.S. The Semiconductor Industry Association reports that the act, as of the end of 2022, had driven $210 billion of private investment across 19 states for building domestic manufacturing capacity and has created 44,000 new high-tech jobs in addition to thousands of jobs for supporting the industry.

The inflation Reduction Act, which provides $500 billion in new tax breaks and spending to promote clean energy, reduce health care costs and increase revenues from taxes is also increasing manufacturing by stipulating that electric vehicles must meet thresholds for being built domestically in order to quality for tax credits. The same subsidies are stoking demand for electric vehicles among the general public. A long list of automobile and battery manufacturers have recently responded to the legislation by announcing plans for expanding their plants or building new factories, with Tesla ringing in 2023 by disclosing it is investing $3.6 billion in its Gigafactory in Sparks, Nevada, which in addition to currently manufacturing batteries will be used to produce electric semi-trailer trucks.

- Geopolitical risks, such as China’s efforts to limit Taiwan’s autonomy and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, are another factor. China has been increasing its military buildup and exercises near Taiwan and if it escalates its efforts to control the island country, the U.S. could be thrust in a difficult position. China is the world’s largest manufacturer, so a conflict between the two Asian countries could create significant supply chain disruptions. The war in Ukraine, meanwhile, is troublesome because the country provides half of the world’s neon for semiconductor manufacturing and it is the world’s eighth-largest producer of iron and steel.

The impact

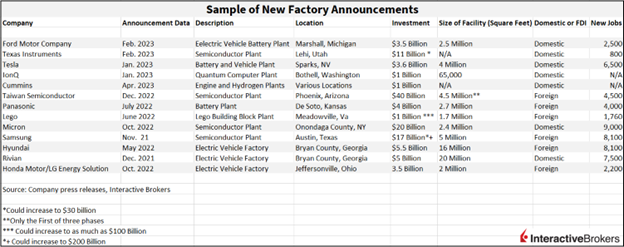

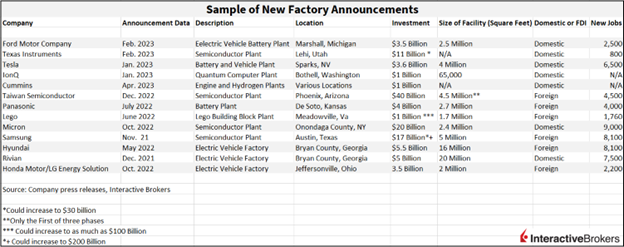

Reshoring and foreign direct investment (FDI) in the U.S. accounted for 364,000 new job announcements in 2022, up from the prior record of 238,000 jobs announced in 2021, according to the Reshoring Initiative. Since 2021, nearly 1.6 million jobs have been announced for reshoring and FDI as companies embark on building multi-billion dollar factories (See table below for examples).

The numbers of workers employed directly by manufacturers that are reshoring or by foreign direct investment plants is impressive, but it is only a small part of the story. Thousands of construction jobs are being created while businesses that provide supplies and services to manufacturers are hiring additional workers and building facilities near new plants so they can better service their clients. Moreover, new factories are increasingly likely to rely on automation to reduce labor costs, which is supporting demand for manufacturing technology.

This huge draw of workers is creating demand for housing near the new factories as well as boosting demand for household goods as newly hired workers furnish their homes. The services industry is also getting a boost in the arm as employees in new factories typically have higher salaries, increasing their disposable incomes for visiting restaurants or enjoying other forms of entertainment. This increased demand for goods and services comes as the Fed is tightening monetary policy to destroy demand across the economy.

The largest impact of FDI and reshoring, however, is that demand for manufacturing employees as well as employees to provide services for these workers is contributing to the country’s labor shortage, which in turn is supporting wage pressures and contributing to inflation. Rather than cut labor expenses by tapping foreign workers, businesses must seek ways to improve their efficiency and they have less flexibility to compete for customers by lowering their prices if they want to maintain profit margins. Workers, for their part, are in better position to negotiate higher wages because they have less competition from foreign labor.

FDI and Onshoring Challenge the Fed

As monetary tightening accelerates, the economy moves closer to a recession, but in this case, the strong job market resulting from reshoring and FDI may allow the Fed to win the inflation battle without creating a large spike in unemployment.

The resulting tight labor conditions have likely required Jerome Powell to be more aggressive with monetary tightening than if reshoring and FDI were absent. As monetary tightening accelerates, the economy moves closer to a recession, but in this case, the strong job market resulting from reshoring and FDI may allow the Fed to win the inflation battle without creating a large spike in unemployment. The Fed has only recently been making progress on inflation and recent data is encouraging, but it clearly faces a strong headwind as businesses increasingly turn to U.S. labor.

Visit Traders’ Academy to Learn More about Economic Indicators.

Join The Conversation

If you have a general question, it may already be covered in our FAQs. If you have an account-specific question or concern, please reach out to Client Services.

Leave a Reply

Disclosure: Interactive Brokers

Information posted on IBKR Campus that is provided by third-parties does NOT constitute a recommendation that you should contract for the services of that third party. Third-party participants who contribute to IBKR Campus are independent of Interactive Brokers and Interactive Brokers does not make any representations or warranties concerning the services offered, their past or future performance, or the accuracy of the information provided by the third party. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

This material is from IBKR Macroeconomics and is being posted with its permission. The views expressed in this material are solely those of the author and/or IBKR Macroeconomics and Interactive Brokers is not endorsing or recommending any investment or trading discussed in the material. This material is not and should not be construed as an offer to buy or sell any security. It should not be construed as research or investment advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security or commodity. This material does not and is not intended to take into account the particular financial conditions, investment objectives or requirements of individual customers. Before acting on this material, you should consider whether it is suitable for your particular circumstances and, as necessary, seek professional advice.

Good article. I moved my manufacturing from California to Thailand in 1985. For routine labor, Thai labor was approximately $3/day, and an MBA could be hired for $350/month. Compare that with the cost of California labor!

Shipping containers to Los Angeles from Bangkok was cheap too.

Today, everything has changed. Labor here is still a lot less than the USA. About $20 to $30 per day now. Still cheap, but 10 times more than 1985. Shipping costs are 5 times more than they were.

I am retired now and my factory is closed. I can understand moving it back to the US were it still operating.