Michael Normyle – Nasdaq’s US Economist joins IBKR’s Andrew Wilkinson and Jeff Praissman to discuss the Consumer Price Index and how inflation effects people at different income levels.

Contact Info:

Email: Michael.Normyle@nasdaq.com

Web: www.nasdaq.com

Summary – IBKR Podcasts Ep. 81

The following is a summary of a live audio recording and may contain errors in spelling or grammar. Although IBKR has edited for clarity no material changes have been made.

Andrew Wilkinson

Welcome to IBKR podcast. This is Andrew Wilkinson. In this week’s edition, we really wanted to drill down into the topic of inflation or otherwise often referred to as the cost of living. In particular, what we wanted to do was to put some things under the microscope and learn more about its impact on consumers. With me is my colleague Jeff Praissman, welcome. How are you doing?

Jeff Praissman

I’m doing well. Thank you, Andrew.

Andrew Wilkinson

Jeff, can you say whether you’ve noticed an impact on your family over the past couple of years in terms of ravaging inflation that we’ve lived through?

Jeff Praissman

I’ve absolutely noticed the impact and probably the two biggest places I’d say are food and gas. It’s easily costing me; I would say $10 to $15.00 more to fill up my gas tank than it did a few years ago and I just feel like food across the board is definitely going up. Whether you’re eating out at a restaurant or whether you’re going to the supermarket, or you know at big box places like Costco, everything is going up basically across all items.

Andrew Wilkinson

Yeah, it’s been tough for a lot of people. Joining us today we’ve got back NASDAQ, US economist Michael Normyle. Welcome, Michael, how you?

Michael Normyle

I’m doing well. Thanks for having me.

Andrew Wilkinson

You’re very welcome back. Let’s start Michael then with some definition here, how does inflation affect the consumer?

Michael Normyle

Well, I think the most direct way to put it is that it affects spending power. And so, in periods of low stable inflation, it’s not actually that much of an issue because oftentimes wage growth will be in line with or even higher than inflation. So, people will have a positive real wage growth in that situation. But in periods where we’re seeing now, you’ve got really high inflation, which erodes your spending power. And then also the flip side is deflation, where prices are falling. And that could be problematic too, because you might see people holding off on spending waiting for their spending power to increase. And that’s bad for the economy in the sense that people are spending less.

Andrew Wilkinson

And that’s been a big problem over decades in the Japanese economy.

Michael Normyle

Right, exactly.

Jeff Praissman

Hey, Michael, how are you? Good to see you again. A term we hear about a lot of news is the consumer price index or the CPI. Could you explain to our listeners what exactly is the CPI and also what is meant by a basket of goods?

Michael Normyle

So, the consumer price index, it’s a measure of inflation created by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which is the one of the government agencies that we have in the US that puts out all sorts of economic statistics. And so, the version that you hear about in the news is CPI-U, which is a measure of prices paid by urban consumers for a basket of goods and services. And so, a basket of goods and services, that’s something that changes over time to reflect what people are actually buying and they have different weights to also reflect the relative importance of what people spend their money on. So, housing has a bigger weight than food or whatnot because you’re going to spend more of your income on housing than on food, for example. And so, it’s very broad and at a high level, you’ll see things like food, energy, shelter, cars, but it also gets very, very granular. So, they’ll have a CPI for apples, one for bananas, they’ll have regular gasoline and premium gasoline, so it gets very in depth.

Jeff Praissman

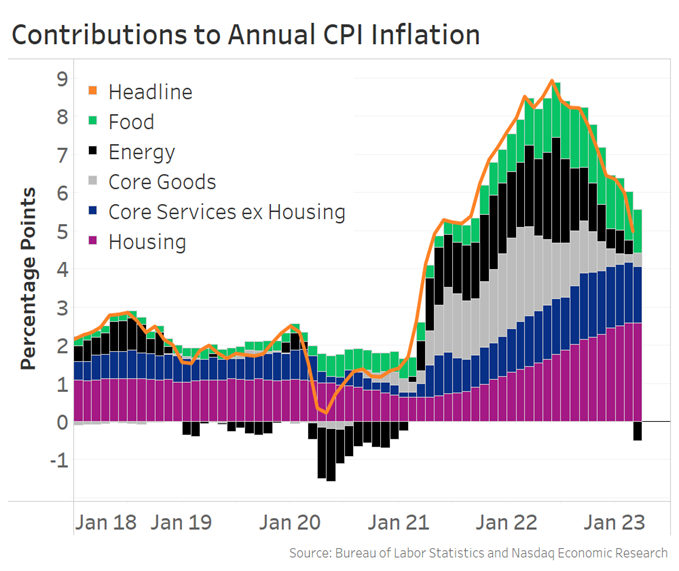

And you’ve provided us with a great chart, which we’re going to include in our study notes, basically charting out the contribution to the annual CPI inflation. You know, I talked a little bit earlier about food and gas, so my own spending. But could you kind of go through how inflation has affected the price of everyday goods and maybe some more examples of the goods that have changed? And how does that change materialize and what you what is the kind of fall back on the consumer from that.

Michael Normyle

You know what happens with inflation really depends on what you’re looking at. So, certain things like commodities can see their prices increase or decrease very quickly. And so that’s why food and energy are excluded from the quote un-quote core inflation measure, which you’ll also hear reported. One of those things, energy, a lot of that has to do with gasoline. So, if you think ahead of the pandemic, if you look at where gasoline was, that inflation was 12% year over year. But a few months later, with everyone stuck at home, people aren’t driving. Demand for gasoline plummeted, so it actually fell to negative 34% year over year. Then again, as things started to normalize, we had vaccines rolling out, demand came back, there was a separate supply issue where during the pandemic, a lot of refining capacity was shut down. So, there was both an increase in demand and a reduction in supply. So, that pushed gasoline inflation up to 56% by mid 2021. Then you know at the start of 2022 you had the war in Ukraine, which again created concerns about supply and so gas reached all the way to 60% year over year inflation. But as all of that stuff has kind of worked its way out, it’s now back down to minus 12% year over year, and then another big category is food inflation. So, if you look at food away from home, for example, food is really divided into two categories. It’s food at home, which is more groceries and food away from home, which is essentially dining. And so, for dining out, you’ve got a mix of commodity prices for the food and then wages for staff and so dining out inflation is up to 9% year over year, which is the highest it’s been since the early 1980s. And a lot of those because during the pandemic and in the recovery, a lot of the labor shortages have been in the leisure and hospitality sectors, which is where restaurants are. And so that’s led to higher wage growth pushing up inflation in that category.

Another example was within the broader kind of goods category. You look at vehicles and so we’ve seen a lot of mixed drivers of inflation there early on the pandemic. When people got their stimulus checks, there’s increased demand for cars. At the same time, that there was a lack of semiconductors available, so that reduced the supply of vehicles. Does that create a bit of a perfect storm for car prices and then at the same time it allowed car dealers to take an opportunity to boost their margins to historic levels. And so, this is something that has been a bit of a topic of discussion lately, which is quote un-quote, greed-inflation, where businesses have been using all the different myriad reasons for inflation going up to increase their prices. And increase them more than inflation. Getting back to cars in the decade prior to the pandemic, new car inflation was essentially ± 1% in that range. And so, it jumped to 13% year over year in early 2022 and at the same time, if you look at the producer price index for trade services for new car dealers, which is essentially a fancy way to say margins for new car dealers that rose to 33% year over year. It had never been above 9% prior to that. That’s a big issue which you’ve seen with cars where it’s demand and supply meeting and pushing car prices up to levels that we really haven’t seen in a long time. And then another issue that’s been kind of front of mind is rent. Prior to the pandemic, rent was usually about 3 to 4%. Currently it’s 9% year-over-year and that’s built over the last couple of years because you’ve got home prices rising, rates rising as the Fed has increased interest rates. And so that makes the monthly cost of you know, getting a mortgage higher. So, that pushes potential buyers out of the housing market, keeps them renters, and then increases demand for rentals, increasing rental inflation.

Andrew Wilkinson

So now Michael, you talked about the urban basket, the Consumer price index for the urban consumer; what I’m interested in is how inflation affects people at different levels of income. Can you talk a little bit about how the ordinary family is affected at different levels? So let let’s take for example, the median household income, which is about $78,000. Those maybe on$125,000 those on $300,000 for example. And what about the impact of inflation on those who have a fixed income? And what about those paying a mortgage compared to those who rent?

Michael Normyle

Starting with the median household income, and like you said, that’s in the $70,000 range. And again, that’s for the household, not for an individual. And so, for people with these median or even lower incomes, the areas that are especially impactful for them are food, energy and shelter and so.

Andrew Wilkinson

Because that takes up a lot of their disposable income.

Michael Normyle

Exactly. It can be 50% or more if you’re talking about lower income quintiles than just those three. And if you’re looking really at the extreme low end, you might see that energy is a little bit less of an issue because you might not own a car. So, gas prices are not impacting you as much, but still food and shelter of course are going to be a really big aspect of your spending, and so actually when you shift to middle income homes, maybe lower middle-income homes, that’s where you start to get squeezed by energy, perhaps a bit more if you own a car and gas inflation is becoming a problem for you. But as you move up the income ladder, higher income people tend to spend more on things like cars and recreation and clothing and travel. So, those categories will become, you know, pay attention more to inflation there.

And then if you go up to say people earning $300,000 or households earning $300,000 in a year, inflation starts to impact you less in the sense of your ability to afford things day-to-day. But then you might become more concerned that you can get a real positive return on your savings and investment. But for people on fixed income, you know that a lot of people on Social Security, you’re going to be looking for your cost-of-living adjustment at the beginning of the year, which is kind of catching up to inflation from the previous year. But you might be in the same bucket where you’re looking at food, energy, housing depending on what exact income level you’re at.

And getting to people who are renters versus having a mortgage, really, the difference is, for mortgages you’re looking at typically a long-term fixed cost. And so, you might refinance it to reduce your monthly payment. But for renters, you’re much more vulnerable to what’s going on in the rental market, and particularly inflation. So, it’s more challenging, certainly for renters where you might get a lease renewal that’s gone up 10%. But if you’re on a fixed rate mortgage, you know that your payments are going to stay the same month after month.

Jeff Praissman

You know, owning a home versus renting – it kind of sounds like inflation’s not really good or bad for homeowners, at least in terms of a monthly payment. But it sounds like it could be really bad for those renting if that’s going to continue to go up.

Michael Normyle

Yeah, I think if you want to get kind of nerdy about it, you could argue that inflation can be, within reason, positive for homeowners. If your mortgage rate is low, when you look at your mortgage rate minus the inflation rate, then your real quote unquote rate could be very low or negative. In essence, you can be paying back your house with money that’s worth less than when you got your mortgage. A lot of people don’t think about things in that term, so, for day-to-day purposes, people on a mortgage are more or less looking at their fixed monthly cost in nominal terms. And if you’re trying to buy a house or sell a house, for example, really what matters is affordability. And so, that’s a mix of inflation, income growth and interest rates. So, inflation plays a role, but again, if income growth is keeping pace, then that’s kind of mitigated. But right now, if you look at it, even with high inflation, a lot of the problem is that mortgage rates are have gone up so much and that’s keeping the supply of homes low because you don’t want to give up a 3% mortgage rate if you were to sell your home and have to move someplace else on top of those higher rates, pricing some people out of the housing market as well.

Andrew Wilkinson

And let’s wrap-up Michael as we turn to talking about policy and the Federal Reserve: The Fed seems obsessed with one specific price index. They look at core services excluding housing, sometimes referred to as ‘super core’ inflation. What is that? Why is it currently their top priority? Is it because it’s easiest to fix or because it will rectify itself overtime? What’s going on?

Michael Normyle

Well, it’s definitely not easiest to fix. So, that’s a big part of the concern is that it’s actually one of the hardest things to fix because this type of inflation is often called ‘sticky’. You know, it’s a term used when it comes to inflation, so something like core services, ex-housing; that’s services excluding food related services, energy related services, and then housing. And so that pretty much leaves stuff that’s mostly driven by wages. And so, wage growth is something that doesn’t typically ramp up or ramp down quickly, unlike the commodities I spoke about earlier. And so, if you’ve got momentum, for example, in wage growth and say wage growth right now it’s around 5%, it isn’t going to drop back to 2% next month, so that’s really why the Fed is concerned because they don’t want elevated wage growth, keeping inflation higher. And that’s a concern because right now the labor market is so tight. Only a tight labor market, where there’s more labor demand than supply, that’s kind of a recipe for higher wage growth. And so, part of the Fed’s goal explicitly has to been to increase rates to cool the labor market, to bring wage inflation down, and eventually that should translate into lower super core inflation. And in the last month or two, we’ve finally seen a little bit of progress there where the wage driven inflation aspects have come down a bit.

Andrew Wilkinson

Michael Normyle, US economist with the NASDAQ thank you very much for joining us today. Jeff Praissman, always a pleasure having you in the room making these podcasts.

Jeff Praissman

Oh, thanks for having me, Andrew. It’s great seeing Michael again.

Michael Normyle

Thanks. Appreciate it.

Andrew Wilkinson

And folks, don’t forget to check out IBKR campus.com for all your financial needs and for more podcasts like this one. And if you’ve enjoyed today’s episode, please do leave us a review wherever you download your podcast from.

Disclosure: Interactive Brokers

The analysis in this material is provided for information only and is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy any security. To the extent that this material discusses general market activity, industry or sector trends or other broad-based economic or political conditions, it should not be construed as research or investment advice. To the extent that it includes references to specific securities, commodities, currencies, or other instruments, those references do not constitute a recommendation by IBKR to buy, sell or hold such investments. This material does not and is not intended to take into account the particular financial conditions, investment objectives or requirements of individual customers. Before acting on this material, you should consider whether it is suitable for your particular circumstances and, as necessary, seek professional advice.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Interactive Brokers, its affiliates, or its employees.

Join The Conversation

If you have a general question, it may already be covered in our FAQs. If you have an account-specific question or concern, please reach out to Client Services.